Neuroscience and Leadership: Bridging Theory and Practice

Neuroscience is reshaping how leadership is understood and practised. By examining how the brain functions under pressure, leaders can improve decision-making, manage stress, and foster better team dynamics. Key principles like neuroplasticity - the brain's ability to rewire itself - offer practical ways to build lasting habits and enhance performance. For example, understanding the brain’s "High Road" (strategic thinking) versus "Low Road" (reactive responses) can help leaders stay composed during crises. Techniques such as controlled breathing, cognitive reappraisal, and focused work intervals are proven to reduce stress and improve outcomes.

Organisations are starting to apply these insights. Companies like Microsoft and Goldman Sachs are using neuroscience-backed methods, such as microlearning and uninterrupted focus zones, to boost productivity and decision accuracy. Frameworks like SCARF (Status, Certainty, Autonomy, Relatedness, and Fairness) highlight how social dynamics impact leadership, showing that small adjustments - like clear communication or offering autonomy - can significantly improve team performance. By understanding these brain-based strategies, leaders can not only improve their own effectiveness but also create environments where their teams thrive.

The question isn’t whether neuroscience can help leadership - it’s how these principles can be integrated into daily practices for better results.

Dr. David Rock - "Understanding the Brain Creates Better Leaders" - NPI 2025

Core Brain Science Principles for Leaders

Understanding how the brain functions under pressure isn't just an abstract concept - it directly influences whether leaders act decisively or react impulsively. Three fundamental neuroscience principles underpin every leadership decision: neuroplasticity, the relationship between emotion and cognition, and the brain's threat–reward systems.

Neuroplasticity and Skill Development

The brain has an incredible ability to rewire itself through focused effort. This process, known as neuroplasticity, involves forming new connections (synapses), strengthening frequently used pathways, and eliminating those that go unused. At the heart of this process lies attention density - the level of focus dedicated to a mental task.

Initially, the prefrontal cortex (PFC) is responsible for complex thinking and planning. However, this part of the brain tires quickly when under prolonged strain. With repeated practice, learned behaviours are transferred to the basal ganglia - often referred to as the brain's "habit centre" - which allows these actions to become automatic and efficient. In practical terms, this means leadership behaviours can shift from deliberate effort to instinctive responses over time.

Several organisations have successfully applied these principles. For instance, Microsoft revamped its leadership training by introducing daily seven-minute digital modules that included retrieval practice. This approach led to a 34% increase in knowledge retention, a 28% improvement in behaviour adoption, and an estimated £190 million boost in productivity. Similarly, Goldman Sachs implemented "focus zones" - 45-minute structured work intervals designed to optimise attention. This initiative reduced decision errors by 21% and cut the time spent on deal analysis by 14% within six months.

Leaders who embrace learning agility, supported by neuroplasticity, are shown to generate 23% more novel ideas. To cultivate these skills, leaders can set aside 25–50 minute blocks of uninterrupted focus, free from digital distractions, to maximise attention density. Additionally, techniques like spaced repetition - presenting learning material in short segments (5–10 minutes) and revisiting it at increasing intervals (e.g., after one day, one week, and two weeks) - can help strengthen neural pathways and enhance skill acquisition.

How Emotion and Thinking Work Under Pressure

When faced with high-pressure situations, the brain operates on two distinct pathways. The prefrontal cortex enables strategic thinking and impulse control, while the amygdala drives emotional responses and threat detection. During heightened stress, the orbital frontal cortex identifies discrepancies between expectations and reality, activating the amygdala's fear circuitry. This process diverts energy from the PFC, impairing rational thought and triggering what is known as an "amygdala hijack."

The difficulty of overriding habitual responses under stress is well-documented. For example, only one in nine patients who undergo coronary bypass surgery successfully adopt healthier habits afterwards - a stark reminder of how resistant the brain can be to change. Similarly, leaders under pressure often revert to ingrained behaviours managed by the basal ganglia, conserving mental resources but potentially limiting adaptability.

To counteract this, organisations like the Mayo Clinic have introduced stress regulation techniques and physiological monitoring for their leaders. These interventions led to a 32% improvement in adopting new technologies and a 28% reduction in burnout symptoms. Leaders trained in neuroscience-based stress management also experienced 27% lower cortisol levels during critical decision-making moments.

One effective strategy for maintaining PFC function during crises is cognitive reappraisal - reframing stressful situations as opportunities for growth. For example, instead of asking, "Why did this failure happen?", leaders could focus on, "What steps can we take to resolve this?" This solution-oriented approach shifts the brain from reactive to strategic thinking, opening pathways for innovative problem-solving.

Threat and Reward Responses in Leadership

The interplay between the brain's threat and reward systems further shapes leadership effectiveness. These systems, which operate continuously, influence decision-making on both a conscious and subconscious level. The "Warning Centre" - a network involving the amygdala, insula, and orbital frontal cortex - generates threat responses that can easily override rational thinking. This is why organisational change often feels like "physiological pain", as it activates fear circuits in the brain.

"Change is pain. Organisational change is unexpectedly difficult because it provokes sensations of physiological discomfort."

- Strategy+Business

Interestingly, dopamine, the brain's "reward chemical", spikes most during uncertain situations. This can be harnessed to motivate teams in high-stakes environments. For example, Unilever created "learning cohorts" consisting of six leaders from different markets. This initiative resulted in a 41% increase in cross-regional innovation and a 26% reduction in mistakes during new market entries.

To shift from reactive to strategic thinking, leaders can develop an internal "dispassionate observer" voice, sometimes referred to as a "wise advocate". This perspective allows for a more measured response to challenges. Additionally, fostering "productive tension" - where ideas are rigorously debated rather than seeking constant consensus - can drive innovation. Research has also shown that expectations shape perception. In one study, the anticipation of pain relief led to a 28.4% reduction in perceived pain, comparable to the effects of morphine. This highlights how consciously managing mental focus can alter brain activity and improve leadership outcomes.

Using Neuroscience to Improve Executive Decisions

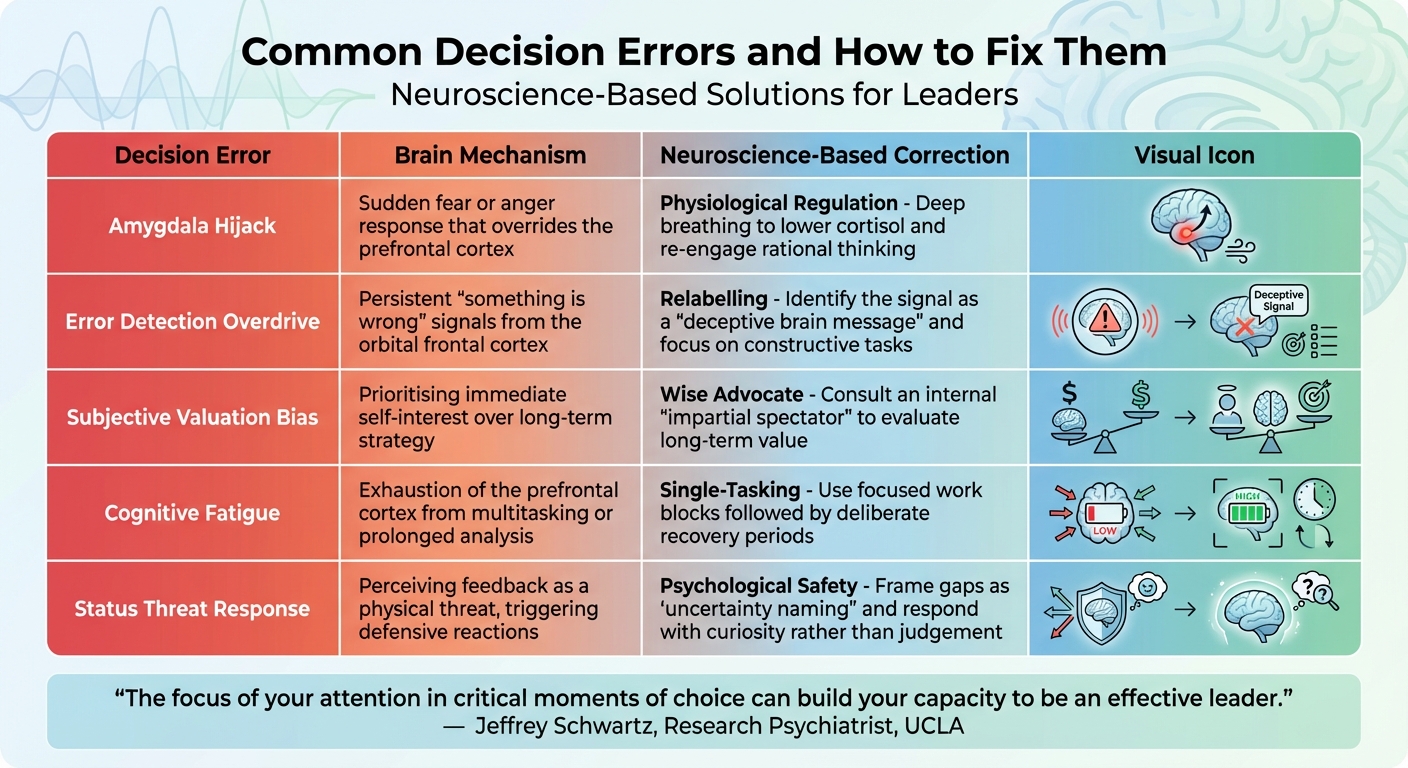

Common Leadership Decision Errors and Neuroscience-Based Corrections

The brain's structure plays a pivotal role in how executives handle high-pressure decisions, determining whether their responses are strategic or reactive. By integrating key neuroscience principles with practical strategies, leaders can refine their decision-making processes. Three neuroscience-driven approaches - cognitive frameworks, micro-skills, and error correction - offer tangible methods to maintain clarity and improve outcomes.

Cognitive Frameworks for Better Decisions

Decision-making processes are influenced by two brain systems: the reflexive (X-system) and the reflective (C-system). The reflexive system, involving the ventromedial prefrontal cortex, amygdala, and basal ganglia, governs automatic responses. Meanwhile, the reflective system, managed by the lateral prefrontal cortex, handles more complex reasoning. By understanding this dual-system model, leaders can identify when they are acting on instinct versus engaging in deliberate analysis.

Training in neuroscience-based decision-making techniques has been shown to reduce cognitive biases by 18% in complex situations. This improvement is underpinned by three key frameworks: dual-system awareness, cognitive reappraisal, and the "Wise Advocate" construct, which promotes a long-term, impartial perspective.

Take Goldman Sachs as an example. The company introduced an attention optimisation programme after discovering that senior leaders spent an average of just three minutes on any given task before being interrupted. By implementing "focus zones" with structured 45-minute work blocks, they reduced decision errors by 21% and cut deal analysis time by 14% within six months. Similarly, IBM launched a metacognitive programme using a "Learning Strategy Navigator" tool to help technical leaders align learning methods with specific challenges. This initiative led to a 34% reduction in the time needed to acquire technical skills and a 41% improvement in applying knowledge across different areas. These examples highlight how metacognitive training can enhance cognitive flexibility and executive function under pressure.

Micro-Skills for High-Pressure Situations

High-pressure situations demand practical techniques to maintain prefrontal cortex function. Controlled breathing, for instance, stabilises the nervous system, reducing cortisol levels and speeding up recovery. Leaders trained in stress management techniques based on neuroscience experienced 27% lower cortisol levels and recovered from stress 34% faster.

The Mayo Clinic offers a compelling case study. During a digital transformation, they introduced a stress regulation programme for clinical leaders, incorporating wearable biofeedback and physiological regulation methods. The results? A 32% improvement in the adoption of technology protocols and a 24% increase in self-reported learning capacity. These programmes teach leaders to recognise early signs of amygdala activation and use pattern interruption techniques to maintain executive function.

Another practical tool is solution-oriented questioning. Instead of asking "why" a failure occurred - potentially reinforcing negative thought patterns - leaders can ask, "What do we need to do to resolve this?" This shift redirects focus towards creating new neural pathways for action, engaging the dorsal prefrontal cortex (the "High Road") rather than the reactive ventral prefrontal cortex (the "Low Road").

Attention-switching rituals also play a role in sustaining performance. Short routines of two to three minutes between tasks can refresh the brain's attention state, preventing cognitive fatigue. Combined with 25–50-minute focused work blocks free from distractions, these rituals help preserve executive function and prevent mental exhaustion.

Common Decision Errors and How to Fix Them

Leaders often encounter predictable neural misfires that can derail their decision-making. By recognising these patterns, they can apply targeted corrections:

| Decision Error | Brain Mechanism | Neuroscience-Based Correction |

|---|---|---|

| Amygdala Hijack | Sudden fear or anger response that overrides the prefrontal cortex. | Physiological Regulation: Deep breathing to lower cortisol and re-engage rational thinking. |

| Error Detection Overdrive | Persistent "something is wrong" signals from the orbital frontal cortex. | Relabelling: Identify the signal as a "deceptive brain message" and focus on constructive tasks. |

| Subjective Valuation Bias | Prioritising immediate self-interest over long-term strategy. | Wise Advocate: Consult an internal "impartial spectator" to evaluate long-term value. |

| Cognitive Fatigue | Exhaustion of the prefrontal cortex from multitasking or prolonged analysis. | Single-Tasking: Use focused work blocks followed by deliberate recovery periods. |

| Status Threat Response | Perceiving feedback as a physical threat, triggering defensive reactions. | Psychological Safety: Frame gaps as "uncertainty naming" and respond with curiosity rather than judgement. |

"The focus of your attention in critical moments of choice can build your capacity to be an effective leader."

- Jeffrey Schwartz, Research Psychiatrist, UCLA

Interestingly, the mental expectation of relief can reduce perceived pain by 28.4% - a result comparable to the effects of morphine. This underscores how managing mental focus not only shapes brain activity but can also influence physical experiences. Leaders who adopt these neuroscience principles are better equipped to navigate high-pressure situations, enabling consistent and strategic decision-making.

Social Brain Science and Emotional Intelligence in Teams

Neuroscience offers fascinating insights into how social dynamics shape team leadership. It turns out that social interactions can activate the brain's survival mechanisms - an idea central to the SCARF framework. For example, when someone experiences public criticism or feels excluded, the brain's dorsal anterior cingulate cortex, which also processes physical pain, lights up. In other words, social pain and physical pain share similar neural pathways, as confirmed by brain imaging studies. This understanding encourages leaders to adopt evidence-based management practices, using frameworks like SCARF to guide their behaviours.

The SCARF Model and Leadership Behaviours

The SCARF framework highlights five key social domains that significantly influence how the brain reacts to situations: Status (how important someone feels), Certainty (the ability to predict what’s coming), Autonomy (having control over decisions), Relatedness (feeling connected to others), and Fairness (perceptions of justice in exchanges). Threats to any of these areas - like micromanagement (which undermines autonomy) or vague communication (which erodes certainty) - can push the brain into a defensive state. This, in turn, hampers cognitive function, creativity, and collaboration. On the flip side, meeting these needs can stimulate the release of neurochemicals that enhance trust, learning, and memory.

"The human brain is a social organ. Its physiological and neurological reactions are directly and profoundly shaped by social interaction."

- Matthew Lieberman, Researcher, UCLA

Leaders can use SCARF audits to identify which domains might be under threat in their teams. For instance, they might ask: Are team members clear about upcoming changes? Is there enough recognition to fulfil their need for status? Since individuals vary in their sensitivities - some may value autonomy more, while others prioritise relatedness - leaders can tailor their approaches to suit these preferences.

Building Psychological Safety for Teams

Psychological safety - the confidence to admit mistakes or voice concerns without fear of losing status - is deeply tied to how the brain processes threats and rewards. In unsafe environments, the orbital frontal cortex generates strong error signals that can overwhelm rational thinking. This explains why innovation often falters in punitive workplace cultures; the brain diverts resources towards self-preservation rather than creative problem-solving.

To foster psychological safety, leaders should focus on intentional communication. For example, instead of asking, "Why did this fail?" - which might trigger a defensive response - they could ask, "What do you need to resolve this?" This approach encourages team members to find their own solutions, releasing neurotransmitters that energise the brain and promote neuroplasticity. Over time, this process helps "rewire" the brain for better problem-solving patterns, setting the stage for continuous improvement in team dynamics.

Practical Adjustments for Social Leadership

Applying SCARF principles in daily leadership practices can significantly boost team performance. Simple adjustments, when consistently implemented, can create environments where team members feel valued and motivated. The table below illustrates how leaders can address common challenges in each SCARF domain and turn them into opportunities for growth:

| SCARF Domain | Leadership Threat | Leadership Reward | Brain-Based Leadership Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Status | Public criticism; being overlooked for opportunities. | Public recognition; seeking expert input. | Offer meaningful feedback and highlight team expertise. |

| Certainty | Ambiguous goals; sudden organisational changes. | Clear expectations; predictable timelines. | Provide regular updates and set transparent goals. |

| Autonomy | Micromanagement; lack of decision-making power. | Delegating authority; offering choices. | Involve team members in decisions and focus on outcomes. |

| Relatedness | Exclusion; "siloed" work environments. | Inclusive activities; fostering collaboration. | Build relationships and encourage teamwork. |

| Fairness | Inconsistent policies; lack of transparency. | Equitable treatment; clear communication. | Explain decisions and apply rules consistently. |

Even small changes can lead to big improvements. For instance, a study of public-sector managers found that while training alone boosted productivity by 28%, adding follow-up coaching increased productivity by 88%. This phenomenon, known as the Quantum Zeno Effect, shows that sustained focus on specific behaviours can stabilise the brain circuits tied to those actions, leading to lasting change. Leaders who consistently reinforce SCARF-positive behaviours through attention and recognition can help their teams achieve far more than traditional training methods alone.

sbb-itb-ce676ec

Building Lasting Leadership Habits with Neuroscience

Adopting new leadership techniques can be an uphill battle, especially when it comes to making them stick. Neuroscience sheds light on why many leadership development programmes fall short: they often clash with the brain's natural tendencies. By aligning with how the brain forms and sustains habits, leaders can create enduring behavioural change.

Using Neuroplasticity for Behaviour Change

At the heart of habit formation lies neuroplasticity - the brain's remarkable ability to rewire itself by creating new connections between neurons. When we adopt new behaviours, the brain's prefrontal cortex - its energy-demanding decision-making hub - takes charge. In contrast, well-established habits rely on the basal ganglia, a more energy-efficient system that operates on autopilot. This explains why adopting change can feel draining and why people often revert to old habits during stressful situations.

One promising approach leverages the Quantum Zeno Effect. This principle suggests that focused, repetitive attention can stabilise neural pathways, helping to embed new behaviours. For example, Microsoft revamped its leadership training in 2025 by introducing daily seven-minute modules that incorporated retrieval practice. These sessions were spaced strategically - after one day, three days, one week, and two weeks - to align with the brain's natural memory consolidation process. The result? Improved retention and more consistent behavioural change.

Another practical technique involves shifting the focus from "why" a problem occurred to forward-looking questions like, "What do you need to resolve this?" This subtle change rewires the brain to form solution-oriented neural connections, paving the way for more constructive outcomes.

These strategies not only help leaders establish new habits but also ensure they remain resilient under pressure.

Stress Management Techniques for Leaders

Stress can derail even the best-laid plans for behavioural change. To safeguard decision-making during high-pressure situations, leaders can adopt stress management strategies that regulate the nervous system and maintain focus.

Controlled breathing is one such technique. By practising a steady five-second inhale followed by a five-second exhale, leaders can achieve heart rate variability coherence, which helps balance the autonomic nervous system. A real-world example comes from the Mayo Clinic, where real-time biofeedback tools improved stress recovery and protocol adherence. Leaders who used these breathing techniques experienced 27% lower cortisol levels during tense moments and recovered from stress 34% faster.

Another method is cognitive reappraisal, which involves reframing challenges as opportunities for growth. This technique helps prevent the amygdala - the brain's emotional response centre - from overpowering rational thought. Unlike mere positive thinking, this approach shifts the brain's processing from the reactive "Low Road" to the more deliberate and strategic "High Road". Goldman Sachs put this into practice by creating "focus zones" and training leaders to work in uninterrupted 45-minute blocks. Within six months, the initiative reduced decision-making errors by 21% and cut the average time spent on deal analysis by 14%.

Designing a Brain-Based Development Plan

To achieve lasting change, a development plan rooted in neuroscience can make all the difference. Such a plan aligns with the brain's natural processes, making it easier to adopt and sustain new behaviours. Key elements include:

- Microlearning Intervals: Break content into five- to ten-minute sessions to avoid overloading the prefrontal cortex.

- Spaced Repetition: Reinforce new behaviours through strategically timed practice sessions.

- Focus Blocks: Create distraction-free periods of 25–50 minutes to maximise concentration.

IBM's "Learning Strategy Navigator" offers a compelling example of this approach. By tailoring learning methods to specific technical challenges, the tool reduced skill acquisition time by 34% and improved the application of knowledge across different domains by 41%. A crucial part of its success was the inclusion of metacognitive development, which encouraged leaders to reflect on their thought processes.

Effective plans also incorporate clear triggers for new behaviours, regular review cycles, and peer coaching. For instance, Unilever's "social brain activation" programme brought together small groups of leaders from various markets. Over 18 months, this initiative led to a 41% increase in cross-regional innovation projects. By tapping into the brain's social nature, the programme reinforced new neural pathways through collaboration and accountability.

Embedding Neuroscience in Organisational Leadership

Incorporating neuroscience into organisational leadership isn't just about understanding brain science - it's about reshaping leadership training and development. While 78% of Fortune 500 companies show interest in neuroscience applications, only 22% have put structured programmes into place. This gap highlights a clear opportunity for organisations ready to align their leadership strategies with how the brain naturally learns and adapts.

Designing Leadership Programmes That Work with the Brain

Effective leadership training needs to respect how the brain processes and retains information. Traditional training methods, such as intensive one-off workshops, often overload working memory, leading to limited long-term impact. Neuroscience suggests a different approach: breaking content into smaller, digestible segments delivered over time. For example, five- to ten-minute microlearning modules spaced out over days or weeks align with the brain's cognitive limits and improve retention.

Microsoft has adopted this method by introducing daily micro-modules with spaced repetition, which has noticeably improved both retention and productivity. This strategy leverages neuroplasticity - the brain's ability to form and strengthen neural pathways through focused attention.

Adding coaching to training programmes further amplifies their effectiveness. Research shows that while training alone can increase productivity by 28%, integrating follow-up coaching boosts this to 88%. Insight-driven learning also plays a key role. Instead of prescribing solutions, neuroscience-based methods use solution-focused questioning, encouraging leaders to arrive at their own insights. IBM’s "Learning Strategy Navigator" exemplifies this approach, helping technical leaders tailor learning strategies to specific challenges. The tool has reduced skill acquisition time by 34% and enhanced cross-domain knowledge application by 41%.

Building Brain-Supportive Environments

The physical and social environments in which leaders operate have a profound impact on cognitive performance. The prefrontal cortex, which handles complex decision-making, is highly energy-intensive and vulnerable to disruptions. Organisations that minimise distractions and protect this vital resource often see improved leadership outcomes.

Goldman Sachs, for example, has implemented uninterrupted work blocks to enhance decision-making accuracy. Psychological safety is another critical factor, as it fosters better stress recovery and innovation. Some organisations have achieved this by using physiological monitoring and real-time biofeedback to create supportive environments.

Social learning environments are equally powerful. Unilever's neuroscience-informed learning cohorts, comprising six leaders from different markets, illustrate this. Over 18 months, the initiative led to a 41% rise in cross-regional innovation projects and a 26% reduction in market entry errors.

Comparing Traditional and Neuroscience-Informed Leadership Development

The table below contrasts conventional leadership development methods with neuroscience-based approaches, highlighting the latter's advantages in fostering lasting behavioural change:

| Feature | Conventional Leadership Development | Neuroscience-Based Development |

|---|---|---|

| Core Mechanism | Incentives and consequences (behaviourism) | Attention density and neuroplasticity |

| Delivery Format | Intensive, one-off workshops | Microlearning with spaced repetition |

| Focus Area | Addressing deficiencies | Building new neural pathways through insights |

| Cognitive Load | High (overwhelms working memory) | Low (respects cognitive limits) |

| Social Context | Competitive or individualistic | Collaborative (activates social brain) |

| Outcome | Short-term compliance, high fade-out | Long-term behavioural change and habit formation |

Organisations adopting neuroscience-based leadership development have reported 12% higher innovation output and a 19% greater success rate in implementing change. These approaches also lead to a 38% increase in employee engagement and a 44% improvement in knowledge retention compared to traditional methods.

"Understanding the neural mechanisms of learning allows us to design interventions that work with rather than against the brain's natural functioning." - David Rock, Co-founder of the NeuroLeadership Institute

The shift towards neuroscience-informed leadership development demands dedication, but the benefits are clear. Leaders trained using brain-based techniques have been shown to experience 27% lower cortisol levels in high-pressure situations. Moreover, organisations that design programmes aligned with cognitive science achieve lasting behavioural changes rather than short-lived compliance.

Conclusion: Connecting Neuroscience and Leadership Practice

Neuroscience offers leaders practical insights to refine decision-making, maintain emotional balance, and strengthen team collaboration. By integrating brain-based principles - such as attention density, cognitive flexibility, and the SCARF model - leaders can achieve outcomes that surpass those relying solely on conventional approaches. Organisations that embed neuroscience into leadership development often see measurable improvements across key performance indicators.

However, effectively applying these principles requires more than just understanding how the brain works. It demands actionable strategies, such as establishing new neural pathways, addressing social threats, and fostering environments that support optimal brain function.

"The focus of your attention in critical moments of choice can build your capacity to be an effective leader." - Jeffrey Schwartz, Research Psychiatrist, UCLA

This insight underscores the essence of neuroscience-informed leadership strategies. Whether it's reframing challenges under pressure or fostering healthy team dynamics, aligning with the brain's natural learning processes helps leaders move from theory to practice.

Leaders operating in high-pressure environments must integrate these neuroscience principles into their daily routines. House of Birch, for example, supports senior leaders by providing tailored advice on incorporating neuroscience into decision-making and leadership behaviours. Through personalised coaching, leaders cultivate the cognitive flexibility and emotional resilience necessary to excel in demanding situations. This hands-on approach transforms theoretical understanding into practical, everyday leadership.

Neuroscience not only sheds light on why change can feel so difficult but also provides concrete tools to overcome these challenges. Leaders who embrace brain-based development often notice marked improvements in stress management and team effectiveness. The real question is not whether neuroscience can enhance leadership, but whether you're prepared to put these principles into practice.

FAQs

How can neuroscience help leaders improve their decision-making and team management?

Neuroscience provides valuable insights that leaders can use to improve their decision-making, emotional awareness, and team interactions. By delving into how the brain functions, leaders can adopt practical strategies to achieve better results and build stronger connections within their teams.

One effective approach is pausing before making critical decisions, which allows the brain's rational processes to take over, helping to reduce impulsive choices. Similarly, practising compassionate leadership - focusing on team members' strengths and listening with genuine empathy - can build trust and encourage collaboration. Another useful technique is visualising calmer responses to reframe emotional triggers, enabling leaders to develop more constructive and thoughtful habits.

Incorporating simple actions, such as celebrating small achievements or reflecting on daily decisions, helps reinforce positive behaviours and supports continuous growth. By integrating these neuroscience-backed practices into their daily routines, leaders can foster a more supportive and effective organisational environment.

How does neuroplasticity contribute to developing leadership skills?

Neuroplasticity, which refers to the brain's ability to reorganise itself by forming new neural connections, is a key factor in leadership development. Through consistent practice of new behaviours, honing decision-making skills, or improving emotional regulation, leaders can strengthen neural pathways that support these abilities while diminishing those tied to less effective habits.

This capacity for change allows leaders to cultivate greater self-awareness, enhance impulse control, and process information more efficiently. Over time, it nurtures learning agility - the ability to adapt swiftly, draw lessons from experiences, and apply those insights in challenging or complex scenarios. With focused effort and reflective feedback, neuroplasticity transforms intentional practice into lasting behavioural shifts, enabling leaders to excel in ever-changing environments.

How can the SCARF model improve leadership and team dynamics?

The SCARF model – representing Status, Certainty, Autonomy, Relatedness, and Fairness – offers a neuroscience-based approach to understanding how people react during social interactions. The human brain is wired to assess situations as either rewarding or threatening, and these five factors play a key role in shaping whether someone feels motivated or defensive.

Leaders can use this model to create a supportive and effective team environment. For instance, providing clear and consistent communication boosts certainty, while allowing team members to make their own decisions enhances autonomy. Recognising individual contributions addresses status, fostering a sense of connection builds relatedness, and ensuring equitable treatment strengthens fairness. When these elements are prioritised, individuals are more likely to feel valued, cooperate effectively, and perform at their highest potential.

Incorporating the SCARF model into leadership practices promotes psychological safety, which in turn supports better decision-making, stronger interpersonal connections, and improved team outcomes.