Behavioral Neuroscience in Leadership: Key Insights

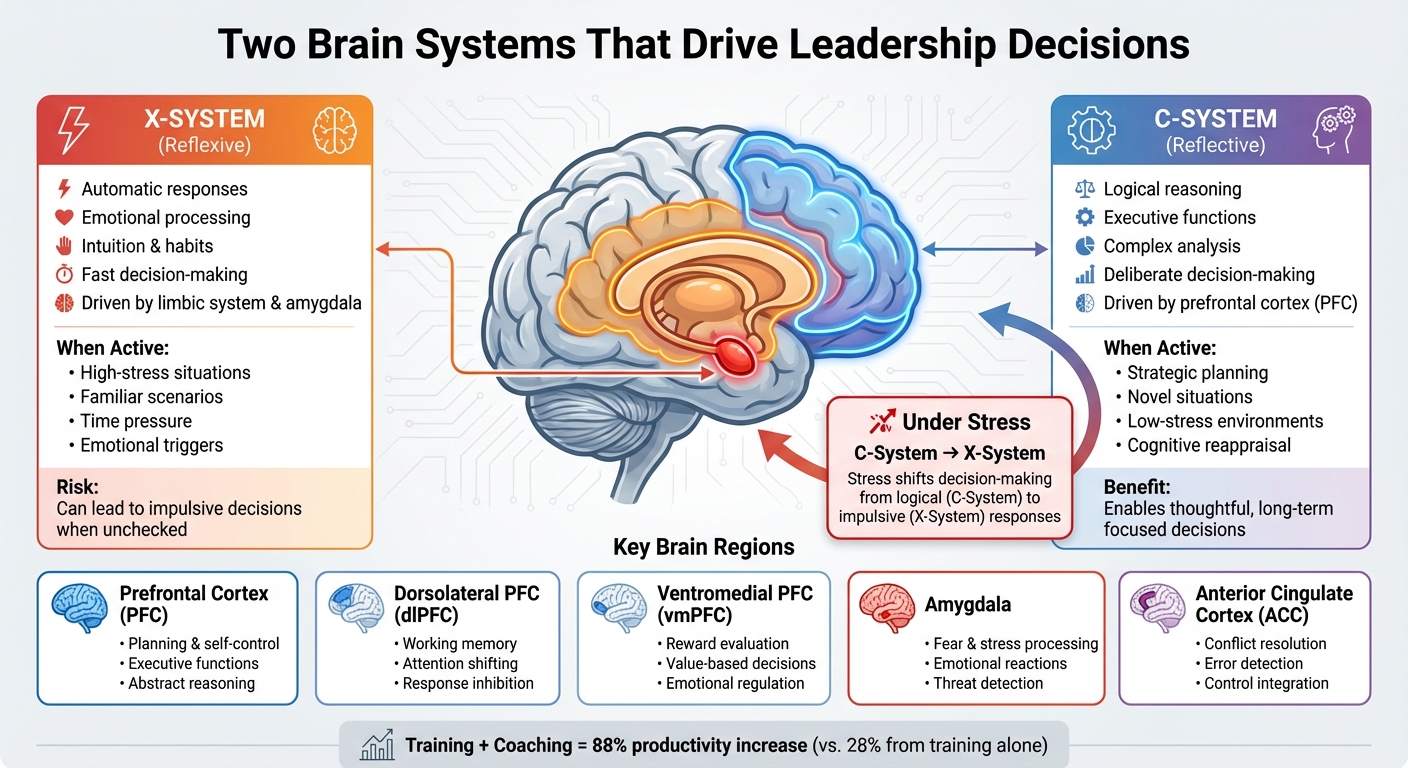

How does neuroscience influence leadership? It reveals how brain systems drive decision-making, emotion regulation, and team dynamics. Leaders rely on two main brain systems: the reflexive X-system (automatic responses) and the reflective C-system (logical reasoning). Understanding these systems helps explain leadership behaviours, especially in high-pressure situations. For example, the prefrontal cortex (PFC) manages planning and self-control, while the limbic system processes emotions like fear and stress.

Key takeaways:

- Leadership decisions are influenced by neural systems like the prefrontal cortex (for logic) and the amygdala (for emotions).

- Stress shifts decision-making from logical to impulsive responses.

- Emotion regulation strategies, such as cognitive reappraisal, improve leadership effectiveness.

- Trust and team dynamics are shaped by hormones like oxytocin and dopamine.

Practical applications include training leaders to manage stress, regulate emotions, and build trust through empathy. For example, mindfulness exercises can reduce stress, while focusing on team members' strengths fosters positive work environments. Neuroscience provides tools to refine leadership skills, ensuring decisions are thoughtful and teams thrive.

Call to Action: To develop effective leaders, organisations should integrate neuroscience-backed strategies into training programs, focusing on stress management, emotional intelligence, and trust-building techniques.

Brain Systems in Leadership Decision-Making: X-System vs C-System

Neural Mechanisms Behind Leadership Decisions

Cognitive Control and Executive Function

Cognitive control and executive function are advanced brain processes located in the prefrontal cortex (PFC). These functions enable leaders to plan, make deliberate decisions, and act purposefully. The reflective C-system plays a supervisory role over the impulsive X-system, allowing leaders to apply abstract decision-making frameworks instead of reacting on impulse. This distinction is especially important in high-pressure situations where the stakes are high.

Effective leadership often hinges on balancing the impulsive, limbic system with the executive functions of the frontal cortex. When the impulsive system dominates and the executive system underperforms, leaders may act recklessly, ignoring long-term consequences. Cognitive control involves suppressing automatic responses and maintaining mental flexibility. Research has shown that transformational leaders typically demonstrate strong inhibition of impulsive reactions, paired with cautious decision-making and adaptability.

Key brain regions like the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC) and anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) play vital roles here. The dlPFC supports tasks like shifting attention, working memory, and suppressing inappropriate responses, while the ACC integrates top-down and bottom-up information, assigning control to other regions as needed. Transformational leaders tend to show lower frontal alpha connectivity, which is linked to greater cognitive flexibility and the ability to adapt decisions to complex, uncertain scenarios. This neural setup allows leaders to build new strategies when faced with unpredictable, long-term challenges.

Beyond these executive functions, leadership decisions also engage neural circuits dedicated to assessing risks and rewards.

Risk and Reward Processing

The ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC) is central to evaluating rewards, making value-based decisions, and managing emotional responses. According to the Somatic Marker Hypothesis, the amygdala generates immediate emotional reactions to potential outcomes, while the PFC evaluates future consequences by triggering bodily cues - signals that say "go" or "stop". The interplay between the reflexive X-system and the reflective C-system shapes how leaders weigh risks and rewards in uncertain situations.

In an August 2018 study published in Science, Edelson and colleagues explored how individuals make decisions involving risk, either for themselves or on behalf of others. Their findings revealed that "responsibility aversion" - the reluctance to make decisions affecting others - was a key factor in leadership. This aversion was linked to connectivity between the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) and the temporal parietal junction (TPJ). As the study explained:

"Responsibility aversion is driven by a second-order cognitive process reflecting an increase in the demand for certainty about what constitutes the best choice when others' welfare is affected".

In February 2024, researchers at Harvard Medical School, including Wei-Chung Allen Lee and Christopher Harvey, conducted a study using a virtual reality maze to observe decision-making in mice. They found that the posterior parietal cortex plays a role in stabilising choices by suppressing alternative options. As Lee noted:

"As the animal is expressing one choice, the wiring of the neuronal circuit may help stabilise that choice by suppressing other choices".

These neural mechanisms highlight how leaders navigate risk and reward. However, stress introduces additional challenges that can disrupt these processes.

How Stress Affects High-Stakes Decisions

Stress significantly alters the brain's decision-making processes, particularly in high-stakes leadership scenarios. When stress levels rise, the amygdala and orbital frontal cortex become more active, diverting energy from the prefrontal cortex, which is responsible for analytical thinking and executive control. Acute stress causes a shift from the reflective, rule-based C-system to the impulsive, automatic X-system. This shift is driven by the SAM system, which releases adrenaline and noradrenaline, and the HPA axis, which produces cortisol for a prolonged stress response.

Elevated levels of noradrenaline and dopamine under stress impair the prefrontal cortex, forcing the brain to rely on habitual responses managed by the basal ganglia. The prefrontal cortex, which processes new information and supports working memory, requires substantial energy, whereas the basal ganglia handle routine tasks more efficiently. Under stress, the orbital frontal cortex frequently signals "errors", leading to impulsive actions and diminished rationality.

Leaders can counteract these effects by adopting specific strategies. Techniques like cognitive reappraisal and mindfulness training help regulate emotional responses and maintain focus during challenging situations. Creating supportive environments, such as private spaces for reflection or structured team discussions, can reduce cortisol levels and alleviate emotional strain. Additionally, the SCARF model - which addresses Status, Certainty, Autonomy, Relatedness, and Fairness - can help minimise stress responses within teams. Neuroscientist Jeffrey Schwartz explains:

"The mental act of focusing attention stabilises the associated brain circuits".

Emotion Regulation and Self-Control

How Leaders Regulate Emotions

For leaders, managing emotions effectively hinges on the interplay between brain regions responsible for cognitive control and those generating emotions. Leaders who employ antecedent-focused strategies, such as cognitive reappraisal, can reframe the meaning of a situation before emotions fully take hold. This approach helps to minimise negative emotions, reduce activity in the amygdala (the brain's emotional centre), and conserve mental energy for decision-making and task performance. On the other hand, response-focused strategies like expressive suppression - where emotions are masked outwardly - are less helpful. Suppression doesn't lessen the internal emotional experience, demands significant mental effort, and can even impair memory.

Professor James J. Gross from Stanford University succinctly describes emotion regulation:

"Emotion regulation is the process by which individuals influence which emotions they have, when they have them, and how they experience and express these emotions".

Effective emotion regulation allows leaders to move from instinctive, habitual reactions - referred to as "model-free" decision-making - to more considered, goal-driven "model-based" approaches. However, acute stress can disrupt this process by impairing working memory, particularly in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, which is crucial for maintaining executive control. Leaders can counteract such effects by using situation modification strategies. For instance, employing humour or steering conversations in a different direction can help diffuse the emotional weight of challenging situations.

Impulse Control and Building Leadership Habits

Leadership also requires balancing impulses - driven by the brain's mesolimbic dopamine system, ventral striatum, and orbitofrontal cortex - against the brain's capacity for self-restraint, which is supported by the prefrontal cortex. However, sustained effort in self-regulation can lead to self-regulatory depletion, where the mental resources needed for discipline and good judgement become exhausted. This depletion increases the likelihood of lapses in control, such as impulsive decisions or emotional outbursts. Research suggests that people fail to resist temptations around 20% of the time, highlighting the challenge of maintaining consistent self-control.

Different regions of the prefrontal cortex play distinct roles in self-regulation, including working memory, response inhibition, goal-setting, and conflict resolution. Professor Kevin N. Ochsner of Columbia University explains:

"Reappraisal depends upon interactions between prefrontal and cingulate regions implicated in cognitive control and systems like the amygdala and insula that have been implicated in emotional responding".

One study focusing on high-level managers found that neurofeedback training helped improve reaction times, shifting decision-making from automatic responses to more thoughtful, deliberate actions. This kind of training enhances interoceptive awareness - the ability to sense internal bodily states - which helps leaders maintain emotional balance and reduce impulsive reactions during high-stakes situations. Researcher Pierpaolo Iodice elaborates:

"The improved ability to manage one's own reaction to stress enables a reduction in instinctive behaviour during a probabilistic choice task".

These self-regulatory techniques are critical because a leader's ability to maintain composure and control directly shapes the emotional environment of their team.

Emotional Contagion and Team Dynamics

Beyond self-regulation, leaders must also manage how their emotions affect team dynamics. Interestingly, verbal communication accounts for just 7% of how people form opinions about a leader; the remaining 93% comes from behaviour and non-verbal cues. When leaders display behaviours that provoke fear or stress, they can activate "fight, flight, or freeze" responses in their team members. This reaction temporarily limits the brain's capacity for complex thinking and decision-making.

A practical example comes from a marketing executive at a large engineering firm. Her inconsistent behaviour - switching between being highly engaged and emotionally distant - eroded trust within her team. By becoming more self-aware and openly communicating her need for reflection, she improved team morale within a month, ultimately earning a promotion to the C-suite.

Suzie Bailey and Anna Burhouse, experts in leadership and quality development, stress the importance of emotional containment in leadership:

"Compassion is vital for leadership, because at its heart, compassion is empathy in action. It helps you to see things from the other person's point of view and understand why they acted as they did".

Research conducted by Gallup, involving over 8 million interviews, underscores the importance of relationships at work. Employees who have a "best friend" at work are seven times more likely to be engaged in their roles. Furthermore, around 80% of organisational improvement stems from relational factors, with only 20% attributed to technical skills and tools. This highlights the profound impact of emotional intelligence and interpersonal connection on team success.

The Leader’s Brain: How Neuroscience Can Advance Managerial Decision Making

sbb-itb-ce676ec

Social Neuroscience of Trust, Authority, and Influence

Delving deeper into the neural mechanisms and emotional dynamics behind leadership, the social neuroscience of trust, authority, and influence provides fascinating insights into how these elements shape effective leadership.

Empathy and Perspective-Taking

Empathy in leadership operates on two levels: understanding another person's perspective, known as cognitive empathy, and sharing their emotional experience, referred to as affective empathy. When leaders engage in both forms of empathy, they activate the prefrontal cortex, which helps them move beyond instinctive, reactionary behaviours. This cognitive flexibility enables leaders to consider multiple perspectives, a critical skill for resolving conflicts and managing diverse stakeholders effectively. Research suggests that the human brain is inherently wired for social interaction, with evidence showing that even in infancy, complex social emotions begin to emerge.

Rather than offering solutions outright, effective leaders use solution-focused questioning to encourage self-reflection among team members. This approach has been shown to stimulate gamma bursts in the brain, which are associated with forming new neural connections. Interestingly, while training programmes alone can improve productivity by 28%, adding follow-up coaching that emphasises empathy and perspective-taking can increase productivity by as much as 88%. The SCARF model, which highlights the importance of social connection and fairness, aligns with this approach. By addressing employees' needs, leaders activate social exchange mechanisms, prompting team members to respond with positive behaviours that often exceed the scope of their formal responsibilities.

These empathetic strategies not only strengthen relationships but also establish the neural foundation for trust and collaboration.

The Neural Basis of Trust and Cooperation

Trust is not just an abstract concept; it is deeply rooted in neurobiology, involving specific brain regions and hormones. The ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC) plays a central role in processing trust-related information and guiding decisions in social contexts. When this region is activated, individuals are more likely to trust others, especially in collaborative environments. Simon L. Dolan, an expert in the neurobiology of trust, highlights this connection:

"Understanding the neurobiology of trust reveals the profound impact that brain mechanisms, neuropeptides, and neurotransmitters have on trust-building within organisations."

Oxytocin, often referred to as the "bonding hormone", enhances trust by reducing fear responses in the amygdala and promoting positive social interactions. It is released in response to cues such as eye contact and physical touch. Studies show that individuals who receive oxytocin are more inclined to trust their leaders and work effectively in teams. Intriguingly, research using intranasal oxytocin has demonstrated that it can improve the recognition of facial expressions, further supporting empathetic leadership. Dopamine also plays a vital role by driving motivation and reward processing, while the amygdala regulates emotional responses. High cortisol levels, often a result of stress, can disrupt decision-making and negatively impact trust dynamics. These findings underscore the importance of understanding the biological factors that underpin trust-based leadership.

Power, Status, and Leadership Behaviour

Social hierarchies are inherently processed by the brain, and the SCARF model - comprising Status, Certainty, Autonomy, Relatedness, and Fairness - provides a useful framework for understanding this. In particular, the concept of Status reflects the brain's sensitivity to social rank and one's relative position within a hierarchy. When leaders act in ways that threaten an employee's sense of status or autonomy, it can trigger the release of stress hormones like cortisol and adrenaline, activating a threat response. On the other hand, positive social interactions and recognition can stimulate dopamine release, fostering a sense of well-being and engagement.

Threats to status often engage the orbital frontal cortex and the amygdala, redirecting energy away from the prefrontal cortex. This shift can lead to impulsive or overly emotional reactions, even when feedback is well-intentioned. Additionally, many routine leadership behaviours are governed by the basal ganglia, while novel tasks require the prefrontal cortex for conscious, deliberate attention. This distinction explains why organisational change can be so challenging - it forces the brain to transition from habitual, efficient processing to more effortful, conscious thought. Leaders also rely on "mental maps", or internal frameworks, to interpret their environment. For example, seeing employees as "troubled children" might focus attention on complaints, while viewing them as experts can help uncover valuable insights. Recognising these mechanisms allows leaders to manage social pressures and create a cohesive team dynamic.

David Rock, founder of the NeuroLeadership Institute, succinctly captures the value of integrating neuroscience into leadership practices:

"Brain research can help people understand how other bodies of knowledge fit together."

There is a growing shift in leadership styles, moving away from traditional "command and control" methods towards approaches that emphasise trust, empathy, and shared goals. This evolution is particularly relevant as younger generations, including Gen Z and Millennials, now make up 38% of the global workforce - a figure expected to rise to 58% by 2030. These demographic changes highlight the increasing need for leadership that prioritises connection, understanding, and adaptability. The neural understanding of social hierarchies offers valuable insights into how leaders can navigate these changes effectively.

Applying Neuroscience to Leadership Development

Evidence‑Based Leadership Development Principles

To effectively incorporate neuroscience into leadership development, training programmes must be designed to engage the brain's prefrontal cortex. This part of the brain, which governs decision-making and problem-solving, thrives on active, hands-on learning rather than passive lectures or presentations.

Consider this: even after undergoing life-threatening coronary bypass surgery, only 1 in 9 people successfully adopt healthier habits. This highlights why traditional training methods often fall short. For leadership development to succeed, it should focus on repeated and purposeful practice of new mental patterns. This approach helps stabilise neural pathways. Instead of overwhelming participants with infrequent, lengthy sessions, programmes should break learning into smaller, more frequent segments. This aligns with the brain’s limited working memory capacity, which can easily become fatigued.

Another effective strategy is the use of solution-focused questioning. For example, asking, "What steps can you take to address this issue?" encourages moments of insight and helps reduce resistance to change. A study involving 31 public-sector managers demonstrated the effectiveness of this approach - adding follow-up coaching to traditional training significantly improved outcomes.

The SCARF model provides a helpful framework for reducing social threats and increasing rewards in five key areas: Status, Certainty, Autonomy, Relatedness, and Fairness. For instance, when giving feedback, leaders should focus on work outcomes rather than personal traits to protect an employee’s sense of status. Similarly, during organisational changes, offering clear timelines and highlighting areas of continuity can minimise stress and resistance by calming the brain’s error-detection response.

Building on these principles, it is essential to use robust assessment tools to measure both behavioural changes and underlying neural shifts in leadership development.

Assessment and Measurement Approaches

Evaluating the impact of neuroscience-informed leadership programmes requires tools that capture both observable behavioural changes and underlying neural mechanisms. For example, pre- and post-intervention surveys using structured questionnaires - often on a 5-point Likert scale - can reveal shifts in employees’ perceptions of leadership, workplace climate, and performance. A study conducted between 2021 and 2023 in Gran Canaria, Spain, offers a compelling example. Over six months, 150 lower-level employees and 25 middle managers across four hotels participated in a programme that used a 17-item questionnaire to assess the influence of "affective events" on leadership perception. The results showed that neuroleadership interventions significantly improved leadership evaluations compared to a control group of employees who did not participate.

Complementary tools like 360-degree feedback allow organisations to gather anonymous input from colleagues, identifying consistent trends in leadership qualities and behavioural changes post-training. Instruments such as DISC, which evaluates observable behaviours and responses to challenges, are also widely used to gauge leadership effectiveness.

In addition to these tools, organisations should monitor neurological safety metrics. These include tracking errors, employee engagement levels, and mental resilience to ensure leaders are not unintentionally triggering "threat" responses - such as fight, flight, or freeze - in their teams. Suzie Bailey, Director of Leadership and Organisational Development at The King’s Fund, highlights the importance of this:

"If leaders and managers behave in ways that scare people, keep them 'on edge' or make them think they are under threat, the fear and stress people experience tend to trigger our most basic survival tactics, fight, flight and freeze responses."

These assessment practices not only quantify the effectiveness of leadership programmes but also guide the development of ethical and culturally sensitive leadership strategies.

Ethical and Cultural Considerations

As neuroscience gains traction in leadership development, it is vital to ensure its application is guided by ethical principles and cultural awareness. One major concern is the spread of "neuromyths" - misusing neuroscience to justify methods that lack proper evidence. Hagar Goldberg from the University of British Columbia cautions:

"The current gap between the high demand and limited supply may lead to misuse of neuroscience in pedagogy (e.g., neuromyths or the justification of educational methods based on limited to no evidence)."

Cultural context also plays a significant role in shaping leadership perceptions. While Western models often emphasise individualism and ego-centric leadership, many non-Western cultures prioritise socio-centric approaches, where cognition and emotions are deeply rooted in social surroundings. For instance, a mirror self-recognition study in Kenya involving 104 children found that only 2 removed a sticker placed on their foreheads. This contrasts with Western populations and illustrates how cultural context shapes self-awareness.

Another critical aspect is neurodiversity. Around 20% of the population is neurodivergent, including individuals with ADHD, autism, and dyslexia. Leadership strategies must accommodate these differences rather than defaulting to a "neurotypical" standard. Neuroscience reframes neurodiversity as a natural result of experience-dependent neuroplasticity, rather than a deficit. Additionally, leaders or team members affected by trauma may face challenges with compromised neuroplasticity. As Goldberg explains:

"A surviving brain is not a learning brain."

To address this, leadership programmes should prioritise creating psychologically safe environments that allow the brain to transition from survival mode to learning mode.

On an ethical level, neuroscience encourages a shift away from the Homo Economicus model - which views people as isolated, rational agents - towards a Homo Relationalis perspective. This framework recognises the brain as a social organ, emphasising that leadership is a relational process shaped by interactions between leaders and their teams. This perspective underscores the importance of fostering ethical, inclusive, and relational leadership practices that resonate across diverse cultural contexts.

Conclusion

Behavioural neuroscience has reshaped traditional views on leadership, offering a more nuanced understanding of how emotions and cognition interact. Modern neuroscience reveals that emotions act as the brain's initial response to stimuli, shaping and guiding our cognitive processes. As Herbert Simon observed, any comprehensive theory of human rationality must account for the role of emotions. This perspective challenges outdated "carrot and stick" leadership models, encouraging approaches that align with the brain’s intricate systems.

These findings have immediate, practical applications for leadership. For instance, leaders who grasp how organisational change activates the brain's error-detection circuits in the orbital frontal cortex and triggers fear responses in the amygdala can implement strategies that complement, rather than conflict with, these biological processes. Evidence supports this: training programmes alone can improve productivity by 28%, but when combined with follow-up coaching - enhancing "attention density" - this figure jumps to 88%. This represents a transformative approach to developing leadership skills.

In high-pressure decision-making, leaders must balance the reflexive X-system (responsible for intuition, habits, and emotional processing) with the reflective C-system (in charge of executive functions and complex reasoning). The somatic marker hypothesis highlights how physical signals, such as changes in heart rate or gut instincts, serve as internal cues - like "stop" or "go" signals - when weighing potential outcomes. Leaders who become attuned to these physiological markers can navigate complex decisions with greater accuracy and confidence.

One of the most compelling insights from neuroscience is the concept of self-directed neuroplasticity. Jeffrey Schwartz’s research demonstrates that:

"the mental act of focusing attention stabilises the associated brain circuits".

This means leadership development should prioritise fostering self-awareness and encouraging moments of personal insight. When leaders experience these "aha" moments, marked by heightened neural activity, the accompanying neurotransmitter release helps to overcome resistance to change and solidify new neural pathways. To achieve lasting impact, organisations must move away from one-off workshops and instead invest in sustained, deliberate practice. This allows these neural circuits to stabilise, embedding effective leadership behaviours into a leader’s natural skill set.

FAQs

How can leaders balance emotional intuition and logical analysis in decision-making?

Leaders can enhance their decision-making by effectively balancing the X-system (emotion-driven, intuitive responses) with the C-system (logical, deliberate thinking). The X-system offers quick, instinctive emotional insights, while the C-system focuses on evaluating long-term consequences, helping to curb impulsive actions. When these two systems are combined, decisions can become both emotionally meaningful and strategically well-grounded.

To put this into practice, leaders might consider techniques such as:

- Pre-mortem exercises: These involve imagining potential failures before they happen, prompting logical reasoning and helping to identify risks early.

- Mindfulness training: Practising mindfulness can improve emotional awareness and self-regulation, enabling leaders to respond thoughtfully rather than react impulsively.

- Structured decision frameworks: Using these frameworks helps to separate emotional responses from analytical evaluations, ensuring a more balanced approach.

By regularly reflecting on the outcomes of their decisions and fine-tuning their approach, leaders can develop a stronger ability to blend intuition with analysis, leading to more balanced and effective decision-making over time.

How can neuroscience principles be effectively applied in leadership training?

To incorporate neuroscience principles into leadership training, it’s essential to focus on three main aspects: brain-friendly learning, emotional regulation, and habit formation.

Start by designing training sessions that are short and focused, lasting around 10–15 minutes. Include breaks for reflection to reinforce learning and help establish new neural connections. Activities such as role-playing and real-time feedback can be particularly effective. These methods engage the brain’s mirror neurons, which play a key role in fostering empathy and understanding different perspectives.

Developing emotional resilience is another critical component. Techniques like mindfulness practices, reappraisal exercises (rethinking challenging situations), and creating a psychologically safe environment can significantly enhance a leader’s ability to manage stress. These approaches also help build trust by stimulating the release of oxytocin, often referred to as the "bonding hormone", which encourages collaboration and stronger interpersonal connections.

Finally, successful habit formation depends on clear goal-setting, immediate feedback, and consistent progress tracking. These strategies tap into the brain’s reward systems, reinforcing positive behaviours and making them easier to maintain in the long term. By aligning leadership training with how the brain naturally learns and adapts, behavioural changes can become more enduring and impactful.

How does stress affect a leader’s ability to make sound decisions?

Stress can heavily influence a leader’s capacity to think clearly and make sound decisions by interfering with the brain's executive functions. When faced with acute stress, the body releases hormones like cortisol and catecholamines. These chemicals shift brain activity away from the prefrontal cortex - responsible for logical reasoning and problem-solving - to the amygdala, which governs more reactive and emotional responses. This shift can disrupt working memory, hinder the processing of complex information, and push leaders to rely on instincts or mental shortcuts. Depending on the circumstances, this may result in decisions that are either overly cautious or unnecessarily risky.

Additionally, stress can cause a phenomenon often referred to as "tunnel vision." In this state, attention becomes overly focused, leading to the neglect of alternative options and a reliance on the most apparent cues. However, research indicates that these negative effects of stress are not irreversible. For instance, neurofeedback training - a method that helps individuals regulate their stress responses - has been shown to restore brain function and enhance decision-making under pressure. With appropriate strategies and interventions, leaders can retain their focus and make well-informed, evidence-based choices even in demanding situations.